PART 3 - The End of Summer A story of the untold childhood

February 22, 2024

This is a subtitle for your new post

Let’s return to the story and find out what happened with Ala. Is she going to be free?

Here it is the final part of The end of summer, a story from my first collection published under Feelings in Staccato: the book of stories.

‘No, I want only Ala.’

I was suddenly wide awake. I leaned on the wall hoping to become invisible.

‘I still do not think that is right.’

‘I am sure you do not, Marcela, but I don’t care what you think. It is the child’s right, and that is all what matters.’ His voice was raised when he added, ‘If you keep insisting, I will stop sending you the money for the house.’

There was silence as I lowered my body to the floor. My back felt the coolness of the wall through my nightgown. I was afraid to breathe.

‘I did not know that you would come back for her,’ my father said tentatively.

‘Before I arrived, I was not sure what I wanted. But I need somebody to live with me. I am old, and I cannot be alone in the house. I know now that Ala is the right one.’ He paused and I sensed the humour in his tone. ‘I thought that you, Marcela, would be pleased to hear this. I feel that you are not very happy with Ala.’

The silence was complete from my mother.

Uncle Albert added, ‘There are servants to keep the house clean and cook, so Ala would only need to keep me company. I still want to read books and newspapers, but my eyes are not the same anymore. And that house is too big and too empty for one person.’

‘Well, we could talk …’

‘Marcela, I do not wish to discuss this matter further with you. All the previous arrangements were made with Nick. As far as I am concerned, your only role in this affair was to spend the money. Now, I want Ala back.’

Another silence, this time so long that I was afraid they would find me crouched on the hall floor, eavesdropping.

My father spoke again, his voice etched by regret.

‘When?’

‘Tomorrow, with me,’ Uncle Albert added softly. ‘Nick, you must know that I value your help. I did not know what to do when both your cousin and aunt lost their lives. But this is the right thing to do.’

My mother changed the subject. ‘I need to prepare your bed, Uncle Albert.’

I tiptoed back to my bed. The silence in the house was ringing painfully in my ears. My night became a sleepless time, tossing and turning in bed with their words in my mind.

When the exhaustion finally caught up with me, I fell asleep and welcomed my dream. It was always the same. In my dream, I was surrounded by the smell of freshly baked bread. The woman was there, smiling at me, with her blue eyes and wide mouth, her grey hair in a bun. I always dreamt her so vividly. She was a fat old lady sitting like a ball, round and dropped on a sofa. You could not see where her torso started or ended. Her shoulders sagged, her back bent — just any woman, a stranger sitting on a sofa. The sofa was a French seater, somehow, I knew that. It was covered with a beige plush, with nice curves on the back rest and hand rests and gilded in gold. The seater looked ugly because of her, and yet there was a tenderness that made me want to join her. In my dream she was not alone. Another silhouette, a thin person, was sitting next to the ball lady: on the edge of the sofa, back straight, head held gracefully, hands resting on her lap. Her face looked delighted. She was beautiful. I could not see her face in my dream, but I knew that.

I shook off the image of the two women in the cold of the night. I wrapped myself in the blanket and warmed myself in its woolly cocoon. I wanted to go back to my dream, but it was too late.

‘Ala, are you going to waste all your morning in bed?’ The indignation in my mother’s voice wiped away the last remnants of my dream. She stood next to my bed and glared, then puffed indignantly and left the room. A few moments later I heard her laughing.

I sat up and hurried through my morning routine. They were all around the breakfast table; when I entered the parlour, my parents and Uncle Albert exchanged looks.

‘Boys, since you’ve finished with breakfast, you should go out and play.’ And out they went.

Uncle Albert had my little treasure in his hand, and I stared at it.

‘Ala, what would you think if I told you that you could come and live with me?’

He looked me in the eye. My father was holding his breath and my mother was covering her mouth with her tanned fingers. They were all waiting for my answer, but all I wanted to know was how Uncle Albert came to hold my bell.

‘I gave you this bell when you were born. It belonged to your great-grandmother. I am happy that you kept it.’

He smiled at me and I smiled back. Was I still dreaming? I sat on the chair next to Uncle Albert and stared at a coffee stain on the starched white tablecloth. I held my palm out and he gently put the bell in my palm. Like so many times in my dreams, I closed my fist around the bell.

‘Yes,’ I said suddenly.

‘Yes what?’ It was my mother.

I looked her in the eye.

‘Yes, I want to go and live with Uncle Albert.’

All hell broke loose. Everybody was speaking: my father asking me if I was sure, Uncle Albert reassuring me that it would be all right, and Lina hiccupping at the door. My mother started to cry — for effect — and then my father hugged me and kissed the top of my head.

In the next hour, Lina prepared a small suitcase for me, as if I were leaving for a week. She was crying all the time and kept coming to hug me. I was holding my bell; I did not let it go for a second. My palm was already sweaty and slippery around the warm silver.

At noon, a big black car stopped in front of the house. The driver did not get out of the car until Uncle Albert called him. He bowed to Uncle Albert and to me, and for a few seconds his eyes hesitated on my face. My mother showed him where our luggage was. He put it in the car then got back in and waited.

I was just standing there looking at a row of ants finding their way across the path in a neat column. It would rain soon; the ants were restless.

My brothers were still out playing. Apparently, nobody bothered to look for them.

Without a word my father pulled me into his arms. When he let me go, my mother came closer and started to wave her pointing finger at me.

‘Now, young lady, never forget where you left from.’ Again, the hoarse voice of Uncle Albert stopped her.

‘Of course, she will not. This is why she is going back now.’ He smiled and grabbed my wrist gently, knowing I was still holding the bell in my hand.

The goodbyes were cut short. We climbed into the back of the big car and Uncle Albert asked the driver to go.

I looked back through the window. I could see my father standing in front of the gate, and he looked somehow stooped, his face ashen. When I could not see him anymore, I turned to Uncle Albert.

‘Will I see them again? My brothers and my father?’

‘Only if you want to and when you want to.’ His voice was soothing.

‘And my mother?’

His face darkened and his voice swished the air.

‘She is not your mother. She never was.’

‘Oh.’ That was the only sound I could utter. And then everything was clear, everything was in its place. Tears of relief poured down my face. She was not my mother, not my mother.

❤❤︎❤︎

Thank you for reading.

Share this post with friends and family

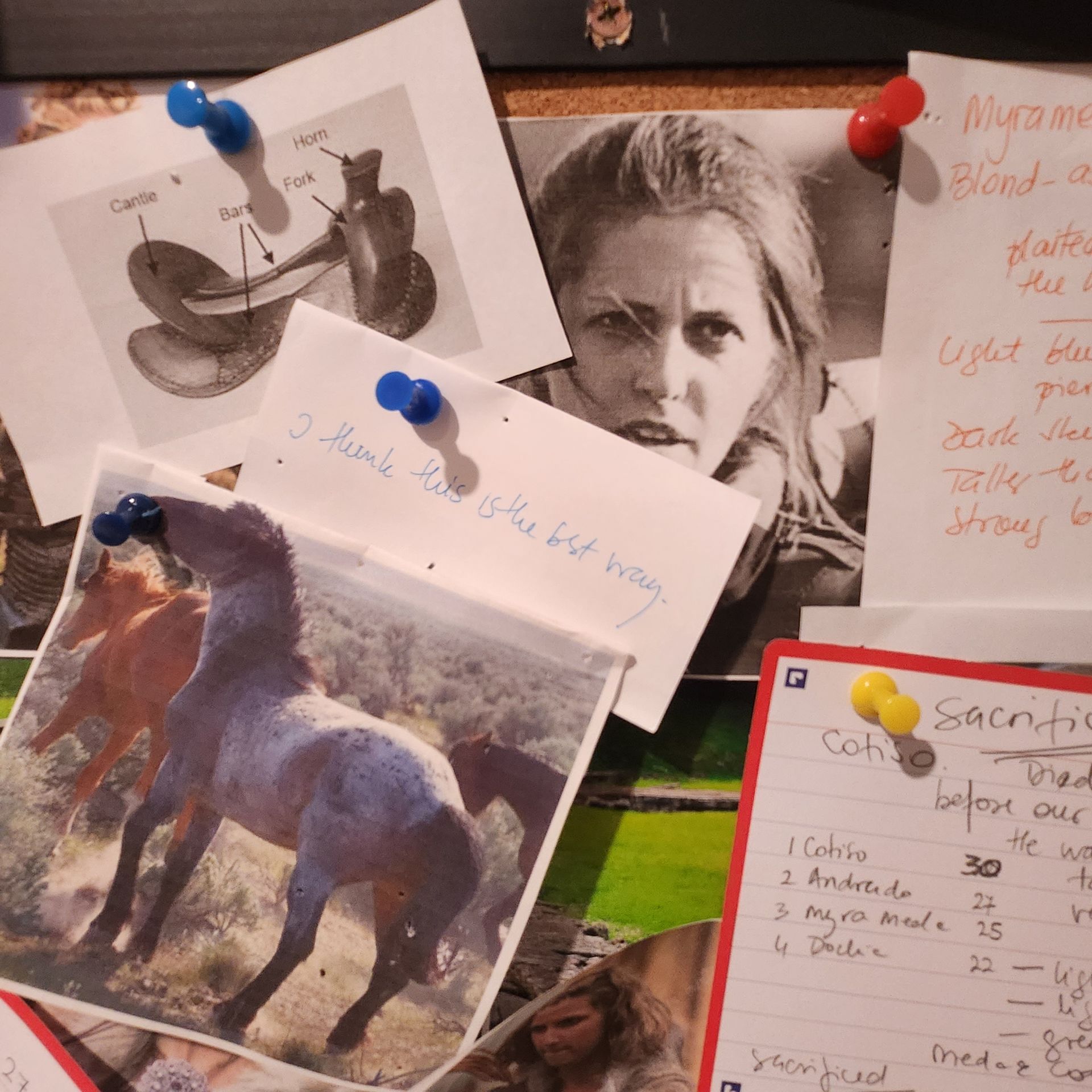

One of the stages when working on a novel is Profiling The Characters and here I am fleshing out my main character - princess Myrameda.

Isn’t that purely delightful? As a writer, you have the chance to create something new, exciting, and a new person altogether. With honesty and willingness to pour your beliefs into it.